By: Germán Bernal

In the south of Tolima, on the peaks of Colombia’s Central Andes Range, springs occur with relative frequency, giving life to rivers, streams and creeks. This is a daily occurrence and is not an exception in the La Alemania, La Primavera and Los Guayabos farms, located respectively in the sub-basins of the Amoyá, Cucuana and Siquila Rivers. Among their productive areas and forests, abundant “water eyes”, as springs are also locally known, emerge. However, these fragile hydric sources are not the only feature that these three properties have in common. Their agricultural and cattle ranching activities represent huge challenges to prevent a negative impact on the environmental patrimony.

Carlos Morales, WCS Colombia’s expert in local conservation strategies, has travelled extensively throughout this mountainous Tolima territory and, consequently, can knowledgably point out rural productivity’s three main challenges to prevent wildlife damage: “the loss of natural forests, extensive livestock farming and direct damage to the hydric resource”.

Situations like those mentioned by Carlos inspired the project Río Saldaña – Una Cuenca de Vida (Saldaña River – a Basin of Life), to search for different strategies that could contribute, in general, to the protection of natural resources, especially water. And one of these strategies are agreement processes, a mechanism that expects to promote a better relationship of farmers with ecosystems, without implying a lower income from their agricultural or livestock farming activities.

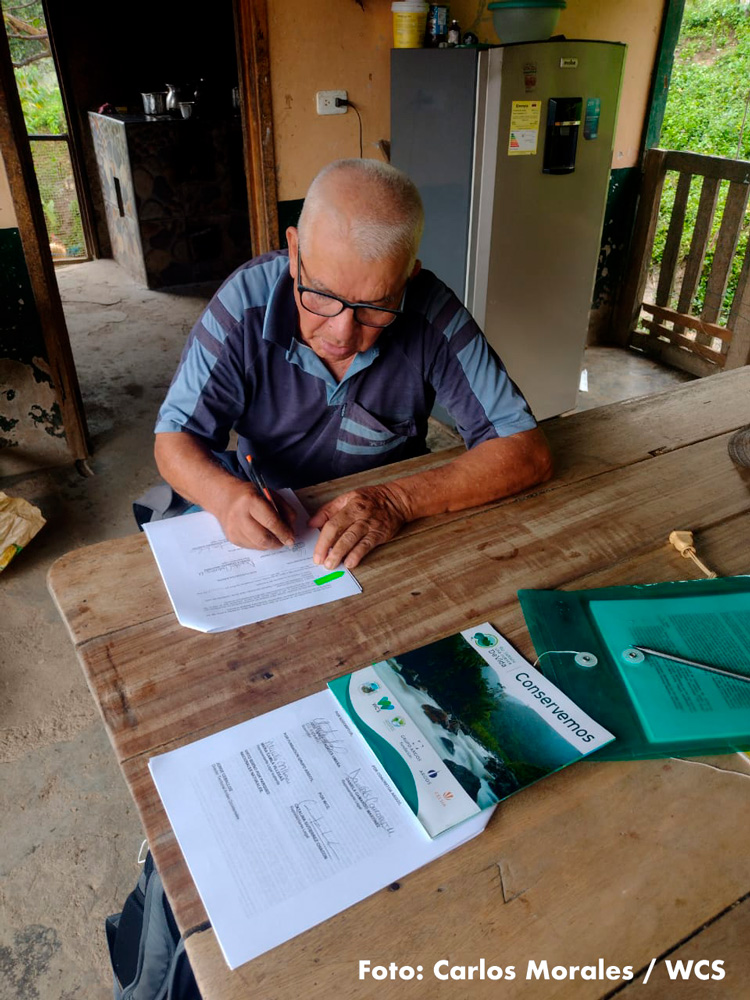

“We have materialized said concerted actions”, adds Carlos, “through what we call voluntary conservation agreements, signed by the farm owners and the partners of the project”, that is technically led by WCS Colombia. It is, in summary, a strategy that aims to contribute to the natural capital with special emphasis on the welfare of the hydric resource. However, making this instrument a reality with each one of the interested owners, is a long and complex process.

Agreements with the heart

The Latin origin of the word “acuerdo”, agreement in Spanish, is the prefix Ad (towards) and Cordis (heart), a pact. Although this may appear romantic and idealistic, it is exactly the purpose of the voluntary conservation agreements: a pact based on the good faith and willingness of the signees, an act that, beyond formal commitments, is made with the heart. The people who sign these agreements are convinced of the enormous value of protecting natural resources. For this reason, these agreements are voluntarily endorsed.

Javier Suárez is in charge of the farm La Alemania, a family inheritance in the rural settlement of San José de Las Hermosas, Municipality of Chaparral. Javier remembers that, even before signing the agreement, his farm had conservation areas. “It was a legacy left by my father. In fact, he began the most conserved area of the farm because he was an enemy of cutting down a tree if it was not necessary. He let them grow and, what was grassland before, is now a small forest.”

Forests are essential for the protection of the hydric resource and, in properties such as La Alemania, with springs on their land, strengthening them is an ethical imperative that, within this strategy, also becomes a technical commitment. "Consequently, as part of the agreement", says Javier, "this farm allotted 8 of its 17 hectares to the conservation of forests, while the other 9 are dedicated to sustainable livestock farming, an activity that is also part of the conservation agreement".

When agreements are signed, farm owners take on different commitments in accordance with the particular characteristics of each farm and the pressures being exerted on the hydric resource. However, in general, they commit to: sustainable productive practices in livestock farming and coffee growing; the protection of forests; the conservation of water sources; and the maintenance, without expansion, of agricultural and livestock breeding frontiers.

Some of the most important actions linked to the agreements are: the planting of native tree species in protected areas; the protection of riparian buffer strips; and intervention in productive activities to make extensive livestock breeding more friendly with natural resources. This includes, for example, the rotation of pastures, the installation of drinking troughs with water overflow control and the production of organic fertilizer. When the properties have coffee production, the handling of honey water that could cause river pollution, is intervened.

Los Guayabos, neighboring the Siquila River, is one of the farms that joined the project. As part of the conservation strategy, 140 trees were planted, to recover the forest. “A year ago, when we planted them, those trees were no higher than 50 to 60 centimeters”, says Martín Bohorquez, administrator of the farm and grandson of the owner. “Now, they measure approximately 1.20 meters, almost double, and the positive effects can already be seen. Cattle do not trample the ground because the forests are isolated and, as a consequence, there are more springs.” The benefits of this strategy will gradually increase and it is expected that they will be maintained in the long-run.

Agreements are not made alone

Besides conviction and good faith, the endorsement of agreements requires a strict institutional organization that will enable a reply to the needs detected. It demands work with partners and the search for economic resources that will make the project viable and support required actions, such as labor, materials, transportation and technical and professional assistance, among other expenses. The owners who sign the agreements receive all these supplies.

Engineer Carlos Morales summarizes the signing process of these agreements as follows: definition of the areas of intervention, that is, identification of the zones with threats for the hydric resource. Selection of the properties that could accept the agreement and information given to the owners and their families of the components and objectives of the project. Finally, those who decide to sign and participate start with the implementation of measures to mitigate the risks for the hydric resource. At the same time, the process of writing up of the documents for subsequent endorsement begins.

The voluntary conservation agreements have a minimum validity of three years. During that time, the actions required for each property are implemented, the necessary support is given and the required monitoring done. For Luis Cerquera, one of the signees in the Cucuana sub-basin, the change begins to be evident with the improvement of the farm. “The project gave us drinking troughs, hoses, insulators and wire for an electric fence. They taught us how to rotate pastures. We have improved our forests. There is still a lot more to be done in order to see more changes, but the process is underway and has been very encouraging.”

In 2016, Río Saldaña – Una Cuenca de Vida (Saldaña River – a Basin of Life) gave its first steps in the structuring and consolidation of this conservation mechanism and it was only possible to sign the first agreements two years later. Since then and until December of 2021, 33 properties have joined this idea. Thanks to this and as more and more owners and organizations embrace this mission, the Amoyá, Cucuana and Siquila Rivers are and will continue being, forever, suppliers of the most vital resource required for our subsistence and wellbeing : water.