Two biologists who just finished their undergraduate studies at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, designed and edited, with their own resources, a successful booklet that describes 20 mammal species recorded in Bogotá D.C. The booklet has been promoted through WhatsApp and social media and motivated by word of mouth. The authors wanted to reach many public and private schools, because all the images in the publication can be colored. They are preparing a second booklet dedicated to the birds of the city.

Sara is interested in zoology and likes to illustrate. Rodrigo is focused on ecology and has an aptitude for design. From this blend of passion for animals, skills for drawing and good taste, the book Mamíferos de Bogotá; y dónde encontrarlos (Mammals of Bogotá; and where to find them), was born.

It is not only a guide showing some of the mammals recorded in Bogotá that have the city as their habitat. It is also a document that brings the imagination to the test when coloring them. A good combination providing information, creating conscience on the importance of local fauna and offering some fun.

The authors, Sara Acosta and Rodrigo Mutis, are two biologists who just finished their undergraduate studies at Universidad Nacional de Colombia, who decided to create this project as a way to contribute to the education of students of public and private schools in the city.

“Our motivation was the lack of appropriation that we have noticed among people in general, and even biologists, for wildlife living in priority zones of Bogotá. Biologists many times prefer to study wildlife from other regions, such as Chocó or the Amazon region, and there is nothing wrong with that, but local species also deserve attention”, says Rodrigo, current director of Herencia Ambiental, who informed that a second book that will be dedicated to birds, could be ready in December.

Initially, the book was distributed as a PDF but, with time, they managed to print 2000 copies, all handled and financed by themselves, with money donated by friends, family members and even some of their professors. It has been shared by Whatsapp, social media and the informal word of mouth force. It can be downloaded for free or bought printed for 25.000 Colombian pesos.

75% of Bogotá is rural

Maybe one of the most relevant messages of the publication is that it shows the readers the existence of species that possibly many Bogotá inhabitants had no information about or did not know that they had very close to their homes, either in the wetlands that still survive between avenues in spite of the growth of neighborhoods and housing developments or in the Cerros Orientales (Eastern Mountains) or in paramos bordering the city, such as Chingaza or Sumapaz.

We must not forget that, of Bogotá’s 163.000 hectares (approximately the area that 340.000 football fields would occupy), 75% are rural, where no more than 60.000 people live. In the other 25%, seven million plus people live.

As per the environmental authority of Bogotá (Secretaría Distrital de Ambiente, District Environment Secretariat), the capital city has a diversity of ecosystems that add up to more than 90 rural types and 400 urban types, where 600 flora species and, potentially, 200 wildlife species live (numbers can vary), of which somewhat more than half correspond to mammals, many of them classified under some degree of threat by national and international authorities.

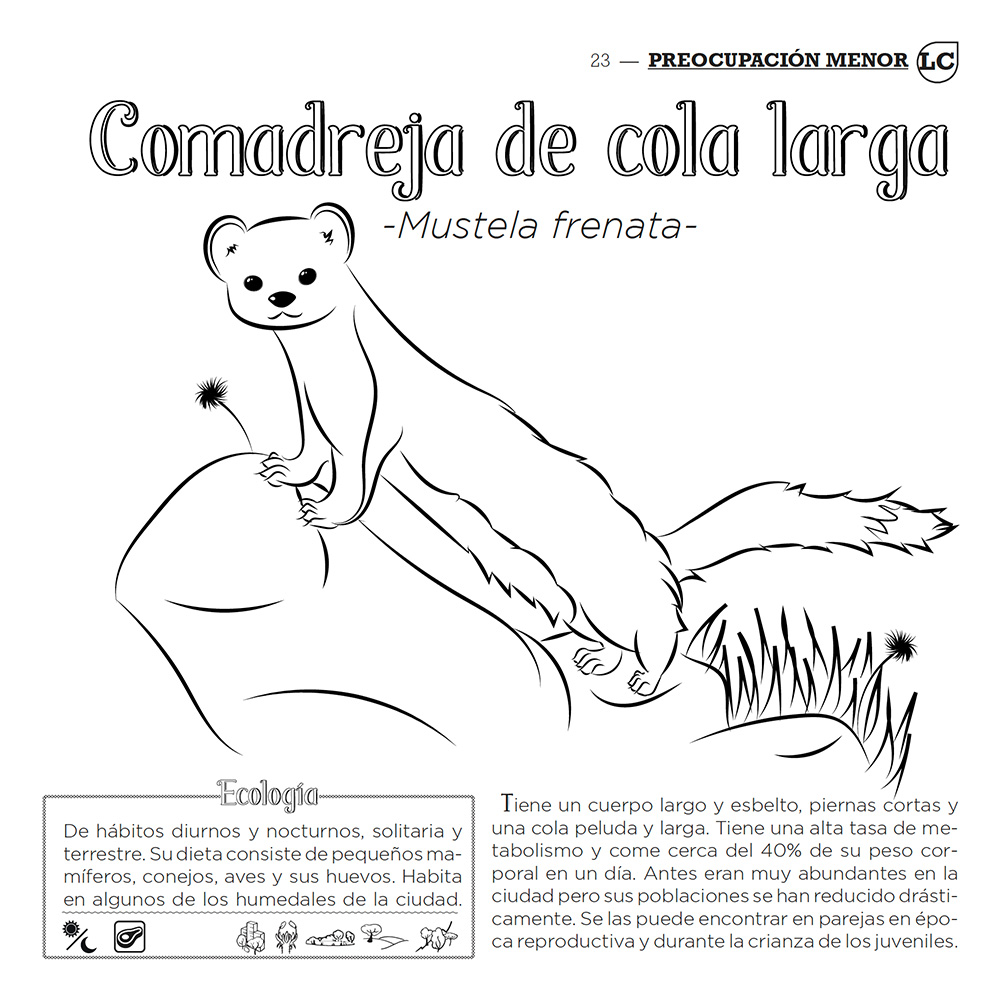

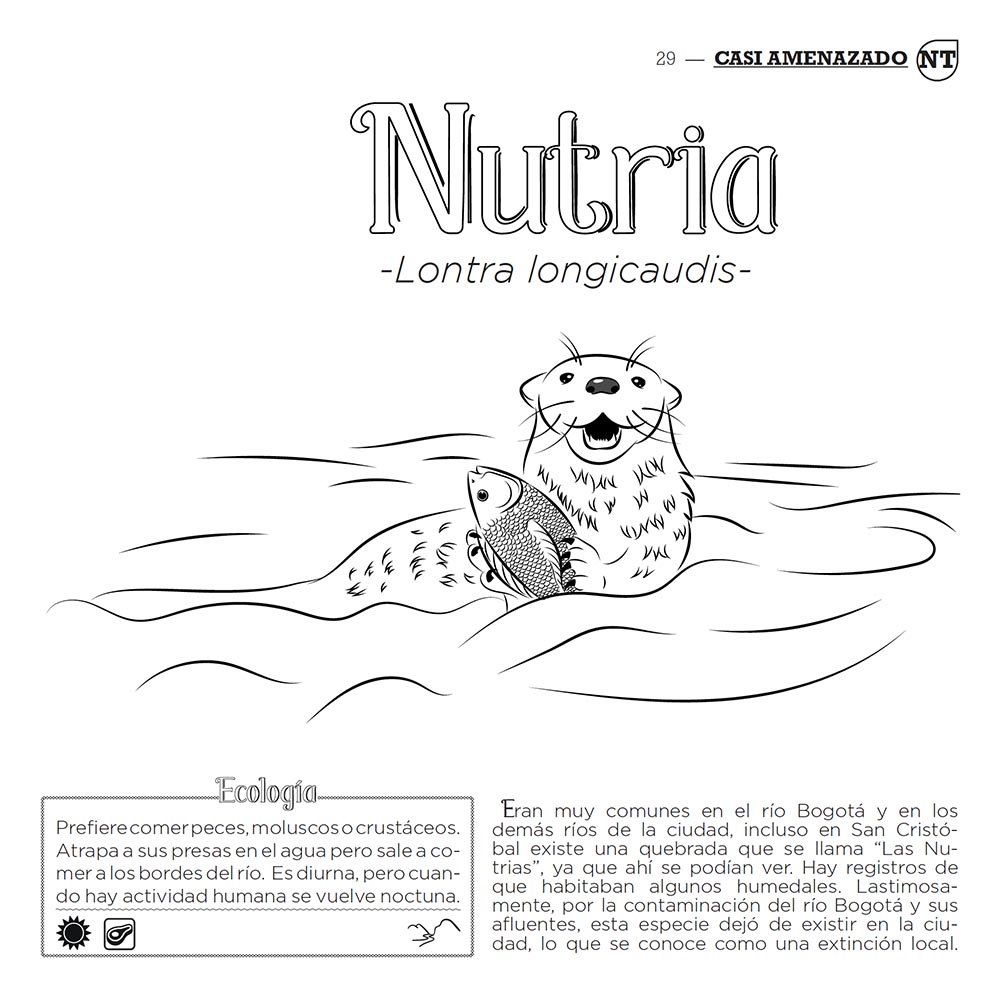

Acosta and Mutis, in their publication, focus on 20 of them, which they identify by their scientific and common names. They compile information on their ecology, for instance, what they eat, if they live in Andean forests, grasslands, rivers, streams or in the urban zone, if they move about at daytime, or by the trees, if they form groups or are solitary, as well as their shelters, among other information.

Is it certain that we share space with a puma?

It is not very usual for Bogotá to be related with being home to an oncilla or tiger cat (Leopardis tigrinus). But yes! It lives in the Cerros Orientales (Eastern Mountains); it is the smallest of the spotted felines. There, it shares space with the crab-eating fox or bushdog, more related with wolves than with the foxes of the northern hemisphere.

And more exactly in the surroundings of what is popularly called ‘cement jungle’, that is, in zones very distant from the city, we can see the puma (Puma concolor), the second biggest feline in the American continent that roves the paramo of Sumapaz. In this same place, decades ago, there were registers and a skull was found of a paramo tapir (Tapirus pinchaque), the smallest of the tapirs living in Colombia, under threat and endangered. To-date, the descriptions or information of its presence in the zone have not been reaffirmed.

The 40 pages highlight two species of bats, of the 23 existing ones: the Bogotá yellow-shouldered bat (Sturnira bogotensis) and the hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus). The first one is a seed disperser and helps in the regeneration of the forest flora. And the second one, sometimes seen in parks, eats moths and other insects (controls infestations), flies very rapidly and has dark hair with white tips, from which its common name originates. But it is not endemic to Bogotá; its populations go from Canada to Argentina.

There was an otter, but it disappeared

A famous mammal that establishes its condition as one of the most charismatic of the capital city is the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), inhabitant of the Chingaza National Park in the locality of Sumapaz, a leaf eater, with horns up to 60 centimeters long and very fast, capable of running at 60 kilometers per hour. And it is not possible to talk about this deer without connecting its habitat with that of the Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus), the only bear in South America. It is an efficient seed disperser, vital for the maintenance of the paramo flora, a shy animal, many times solitary, which runs away from human presence.

The text also covers an important group of small mammals, such as the red-tailed squirrel (Notosciurus granatensis), the mountain paca (Cuniculus taczanowskii), the western mountain coati (Nasuella olivacea), the long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata), Apollinaris’ cottontail (Sylvilagus apollinari), the wild cavy (Cavia aperea), Thomas’s small-eared shrew (Cryptotis thomasi), the Andean white-eared opossum (Didelphis pernigra) and the striped hog-nosed skunk (Conepatus semistriatus). And two mice: the Bogotá grass mouse (Nepmicroxus bogotensis) and the soft-furred Thomasomys (Thomasomys laniger).

“Many people do not respect some of these animals, especially opossums, because they think they are giant rats or overfed rodents. We think that, if there is adequate information on each one, the risk for them may start disappearing”, explains Rodrigo.

The text gives interesting but unfortunate information of the existence in the Bogotá River, until a few years ago, of a long-tailed otter (Lontra longicaudis), that could even protect itself in some wetlands. But the species is now locally extinct due to the pollution of the water.

It is only fair to highlight one of Rodrigo´s phrases, when he says that many people do not know or appreciate what they have. “This is why, he says, part of what we should do to preserve those natural and biological resources is learn from them, because we are lacking a lot of information on their biology. We should show their importance, as part of a strategy of environmental awareness”. Additionally, because these species living in Bogotá, that we now have the opportunity to color, do not deserve the fate of this otter and cannot suffer it. We should feel fulfilled and proud of them.

*To buy the printed book, call Rodrigo Mutis, cell phone 316-5320228